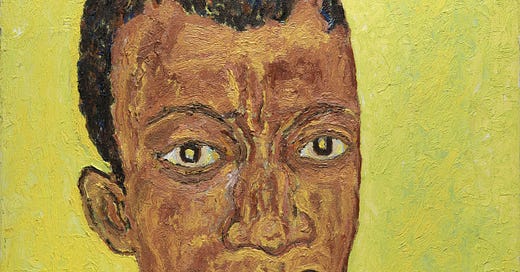

James Baldwin on Art & Writing

I’ve read every nonfiction work James Baldwin’s ever written. It’s kind of insane how he writes with such emotion and feeling. It feels like an unbelievable mix of unfiltered freedom, thoughts flooding out of him — but with this extreme eloquence. I guess that’s what the best people at their craft are able to do — give this feeling of complete freedom and raw expression, while maintaining this incredibly high-quality craftsmanship that feels like second-nature.

I don’t really know why I’m writing this post on him. I think it’s in part because I revisit his essays so often, I wanted to create some compilation of words and essays that have meant something to me, for one reason or another.

“Notes from a Native Son”

Any writer, I suppose, feels that the world into which he was born is nothing less than a conspiracy against the cultivation of his talent—which attitude certainly has a great deal to support it. On the other hand, it is only because the world looks on his talent with such a frightening indifference that the artist is compelled to make his talent important. So that any writer, looking back over even so short a span of time as I am here forced to assess, finds that the things which hurt him and the things which helped him cannot be divorced from each other; he could be helped in a certain way only because he was hurt in a certain way; and his help is simply to be enabled to move from one conundrum to the next – one is tempted to say that he moves from one disaster to the next.

This one is such a beautiful, bittersweet but hopeful framing. It reminds me of the Samuel Beckett line, “i can’t go on. i’ll go on.”

“Why I Stopped Hating Shakespeare”

Every writer in the English language, I should imagine, has at some point hated Shakespeare, has turned away from that monstrous achievement with a kind of sick envy. In my most anti-English days I condemned him as a chauvinist (“this England” indeed!) and because I felt it so bitterly anomalous that a black man should be forced to deal with the English language at all — should be forced to assault the English language in order to be able to speak — I condemned him as one of the authors and architects of my oppression…

My quarrel with the English language has been that the language reflected none of my own experience. But now I began to see the matter in quite another way. If the language was not my own, it might be the fault of the language, but it might also be my fault. Perhaps the language was not my own because I had never attempted to use it, had only learned to imitate it. If this were so, then it might be made to bear the burden of my experience if I could find the stamina to challenge it, and me, to such a test.

Baldwin continues to compare Shakespeare’s language to jazz. He writes of the “bawdiness” of both Shakespeare and jazz, which “revealed a tremendous, loving, and realistic respect for the body.” He’s speaking to something in the uncontained, the free nature that I associate with his writing — from which he felt constricted. Jazz helped unlock that for Baldwin.

Jazz was always played in the house growing up. At first, I hated it, but then — and this is probably the arc for many things you feel you hate at first, if you give it enough of a chance: you grow to appreciate it, then you find yourself loving it. I don’t know. Maybe when there’s something powerful enough that you have a viscerally negative reaction to it, there’s a kernel in there that you should examine. Something’s hitting you deep — and even if you truly hate it, there’s something to take from it that probably shows you what you love. Anyway. Baldwin goes on:

The greatest poet in the English language found his poetry where poetry is found: in the lives of the people. He could have done this only through love — by knowing, which is not the same thing as understanding, that whatever was happening to anyone was happening to him. It is said that his time was easier than ours, but I doubt it — no time can be easy if one is living through it. I think it is simply that he walked his streets and saw them, and tried not to lie about what he saw: his public streets and his private streets, which are always so mysteriously and inexorably connected; but he trusted that connection. And, though I, and many of us, have bitterly bewailed (and will again) the lot of an American writer — to be part of a people who have ears to hear and hear not, who have eyes to see and see not — I am sure that Shakespeare did the same. Only, he saw, as I think we must, that the people who produce the poet are not responsible to him: he is responsible to them.

I think about that above passage a lot. It speaks to so much: empathy, understanding, observing others and exploring the internal and believing — knowing — that the two are linked. Frustration. Seeking something. I don’t know. It’s beautiful he was able to find that connection and unlock that for himself.

It makes me wish I could read Shakespeare without the books the pages that have those little definitions on the left side of the page.

Anyway, I’ll add to these.